ADHD and the Default Mode Network: Balancing High Performance and Burnout

Following on from Day 3, I truly believe that the Default Mode Network (DMN) and ADHD deserve a heavily researched exploration. I was surprised by how strongly I noticed DMN overactivity once I stepped away from a high-pressure work environment. It made me reflect on how I would stay wired for long periods, excelling in fast-paced conditions, before inevitably burning out.

ADHD is more than just inattention or impulsivity; it involves measurable differences in brain network functioning. The DMN—a neural system responsible for mind-wandering, introspection, and self-referential thought—has become a major focus in ADHD neuroscience research. While the DMN typically quiets down when focus is required, in ADHD brains, this suppression is inconsistent (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002). This has far-reaching consequences for attention, work performance, and mental health, particularly in the context of burnout.

This post examines recent peer-reviewed research on ADHD and the DMN, exploring how this neurological wiring can lead to both success and burnout in fast-paced environments.

Neuroimaging Insights: ADHD and a Dysregulated Default Mode Network

Research using fMRI and neuroimaging techniques has revealed clear differences in DMN function in individuals with ADHD. In neurotypical brains, the DMN acts as a background network, deactivating when focus is required. However, in ADHD, this deactivation process is impaired, leading to persistent DMN activity even during tasks (Liu et al., 2024). This phenomenon, known as the “default mode interference” hypothesis, suggests that excessive DMN activation disrupts attention (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002; Rommelse et al., 2008).

Simply put, the brain’s daydreaming network intrudes on its focus network.

Figure 1: The Mind-Wandering Hypothesis in ADHD

Illustration of how DMN and executive networks interact. In ADHD, the salience network, which switches between “wander” and “focus” modes, is dysregulated. This results in excessive mind-wandering, contributing to inattention and performance lapses (Castellanos & Tannock, 2002; Rommelse et al., 2008).

Many neuroimaging studies confirm abnormal connectivity in the ADHD DMN. Findings include reduced internal DMN connectivity (hypoconnectivity) and excessive cross-talk between the DMN and task-positive networks (hyperconnectivity). For instance, one recent study found weaker connections within the DMN but stronger, undue connections between the DMN and attention-related networks (Liu et al., 2024).

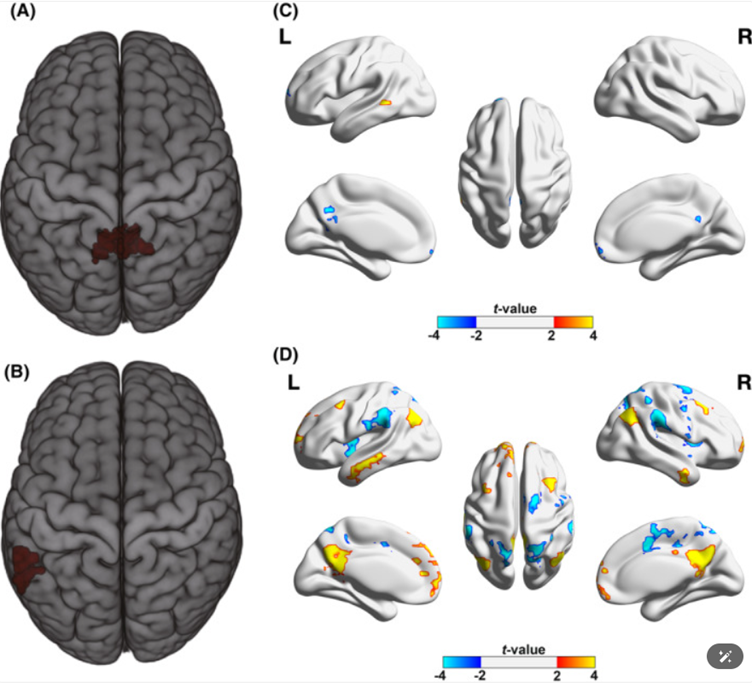

Figure 2: Neuroimaging Findings from Liu et al. (2024)

Key observations from fMRI analysis comparing adults with ADHD to neurotypical controls:

Left precuneus: Altered connectivity affecting introspection and task-switching.

Left middle temporal gyrus: Hyperconnectivity linked to verbal processing and internal dialogue, contributing to distraction.

These findings suggest that brain regions responsible for introspection and focus are less synchronised in ADHD. Consequently, the DMN remains overly active, making it harder for individuals to shift into a task-focused state when needed.

Meta-Analyses of DMN Dysfunction in ADHD

Further supporting these findings, meta-analyses of resting-state fMRI studies highlight atypical DMN-executive network integration in ADHD.

A meta-analysis of 25 studies (nearly 700 ADHD patients) found consistent hyperconnectivity between the DMN and frontoparietal executive networks (Gao et al., 2019).

Research on children with ADHD linked excessive DMN connectivity to increased errors in attention tasks, demonstrating the impact of DMN dysfunction on real-world performance (Duffy et al., 2021).

Essentially, the ADHD brain struggles to suppress the mind-wandering network, causing task-related performance deficits.

DMN Fluctuations and ADHD Task-Switching Impairments

Not only is DMN connectivity altered, but its activity is also highly variable. Studies show:

Children with ADHD display greater DMN fluctuations at rest, indicating less stable background brain activity.

DMN disengagement is slower, meaning that ADHD brains struggle to rapidly switch between tasks.

Neuroimaging shows that unmedicated ADHD children exhibit a DMN connectivity spike right before responding to a task, reflecting difficulty in shutting down the DMN in time (Silberstein et al., 2016).

Stimulant medication (methylphenidate) has been shown to suppress inappropriate DMN activity, improving reaction times and task focus.

Modern neuroimaging portrays ADHD as a disorder of network dysregulation. When the DMN is not properly controlled, we see excessive mind-wandering, inconsistent performance, and attentional blips. However, under the right conditions, the quirks of an ADHD brain—such as creative, spontaneous thought—can become strengths. The next section explores how these neurological traits impact performance in high-demand environments.

Thriving in High-Drive Environments – and the Road to Burnout

Many adults with ADHD excel in high-stimulation, fast-paced environments where novelty and urgency drive performance. A looming deadline or a crisis can trigger hyperfocus, allowing them to operate with intense concentration that is otherwise difficult to sustain.

ADHD Strengths in High-Demand Environments

Research confirms this phenomenon: Sibley et al. (2021) found that ADHD individuals perform better under "high environmental demand" because immediate pressure naturally suppresses the DMN, enabling sustained attention.

💡 Careers Where ADHD Strengths Shine:

Emergency medicine, event planning, and crisis response (high-adrenaline decision-making).

Creative industries and entrepreneurship (rapid ideation and problem-solving).

Fast-moving workplaces with constant novelty and feedback.

ADHD professionals often describe themselves as highly innovative thinkers, excelling in brainstorming, creative problem-solving, and adaptability (Oscarsson et al., 2022). Their ability to think quickly, spot patterns, and handle unpredictability makes them well-suited for these fields.

The Double-Edged Sword of Hyperfocus

However, the same conditions that fuel productivity can also lead to burnout. High-pressure environments often involve excessive workloads, prolonged stress, and unpredictable demands.

🔻 The ADHD Burnout Cycle:

Hyperfocus: Intense engagement at the expense of sleep, breaks, or self-care.

Overextension: Taking on too much responsibility, ignoring exhaustion.

Cognitive and Emotional Depletion: Attention lapses increase, self-doubt sets in.

Burnout & Disengagement: The DMN dominates, leading to avoidance and social withdrawal.

Studies indicate that adults with ADHD face a significantly higher risk of occupational burnout compared to neurotypical peers (Ashinoff & Abu-Akel, 2021). Burnout in ADHD is often characterised by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced self-efficacy, compounded by the additional mental effort required to manage executive function challenges, such as time management and organisation (Stern & Maeir, 2024).

A field study on ADHD employees found significantly higher burnout rates, largely due to difficulty with self-regulation and workload management (Jönsson et al., 2022). In high-pressure roles, simply keeping up demands immense cognitive effort. Many compensate by working longer hours, constantly firefighting, and neglecting personal well-being, leading to mental and emotional depletion. Without structured support, "thriving" quickly turns into barely surviving.

When High Performance Becomes Unsustainable

The same drive that fuels success can also accelerate burnout. Research suggests that ADHD adults often push themselves harder to compensate for executive function difficulties, leading to chronic stress and eventual breakdown (Porto et al., 2024).

Without proactive intervention, prolonged work-related stress leads to:

Declining focus and increased attention lapses.

Diminishing returns on productivity despite extended working hours.

Heightened risk of disengagement, as exhaustion depletes cognitive and emotional reserves.

As ADHD professionals navigate demanding environments, understanding the neurological mechanisms of burnout is crucial. The next section explores how DMN dysregulation contributes to disengagement and the strategies needed to balance high performance with long-term well-being.

Burnout and the Default Mode Retreat: Depersonalisation and Isolation

When ADHD individuals experience burnout, the Default Mode Network (DMN) often becomes an escape route. Rather than efficiently switching between focus and rest, the brain retreats into prolonged disengagement, manifesting as excessive mind-wandering, difficulty initiating tasks, and emotional detachment.

Neurological Mechanisms of ADHD Burnout

Burnout disrupts key neural networks involved in attention regulation and task engagement.

🧠 Key Brain Changes in ADHD Burnout:

Salience network depletion weakens the brain’s ability to transition between focus and rest states, making sustained attention harder (Gao et al., 2019).

Excessive spontaneous mind-wandering emerges when cognitive control weakens, leading to prolonged disengagement (Qian et al., 2024).

DMN hyperactivity prolongs cognitive drift, making it increasingly difficult to re-engage in structured tasks.

What may begin as a brief mental break can spiral into hours of avoidance, further impairing productivity and increasing stress levels.

Depersonalisation: The Psychological Toll of ADHD Burnout

Burnout in ADHD is often linked to depersonalisation—a sense of emotional numbness or detachment from work and self.

📌 Research Highlights:

Depersonalisation is more pronounced in individuals with attentional difficulties, as frequent mind-wandering increases emotional exhaustion (Silberstein et al., 2016).

A study on ADHD college students found a direct correlation between inattention severity and depersonalisation, meaning the more frequent the attention lapses, the stronger the emotional and cognitive exhaustion (Yang et al., 2023).

This experience aligns with burnout narratives in ADHD, where emotional depletion and cognitive overload lead individuals to disconnect from both personal and professional responsibilities.

Social Withdrawal and Isolation: A Vicious Cycle

Neuroimaging studies reveal that lower DMN connectivity in ADHD is linked to impaired social functioning (Cohen et al., 2021). As burnout intensifies, so does social withdrawal. Many individuals describe:

Avoiding colleagues and delaying responses to conserve energy.

Isolating themselves due to feelings of exhaustion or inadequacy.

Struggling to re-engage in social interactions, reinforcing feelings of disconnection.

The DMN’s inward pull, combined with emotional depletion, creates an invisible barrier between the burned-out individual and their external environment.

The ADHD “Shutdown” and Its Consequences

This mental retreat can become a reinforcing cycle:

The more an individual disengages, the harder it becomes to re-engage.

Excessive daydreaming or avoidance behaviours lead to missed deadlines, increasing stress, guilt, and further burnout.

Some researchers describe this phenomenon as an ADHD "shutdown", where the brain essentially disconnects as a protective mechanism—physically present but mentally absent.

Although not formally recognised in clinical literature, it captures the lived experience of ADHD burnout-induced disengagement.

Breaking the Cycle: Addressing ADHD Burnout Proactively

Recognising this cycle is crucial. Preventing ADHD burnout is not just about reducing distraction, but also about addressing the cumulative overload that drives individuals to retreat into the DMN.

The next section explores research-backed strategies for maintaining high performance while safeguarding long-term well-being.

Walking the Tightrope: High Performance Without Burnout

Achieving success while avoiding burnout requires intentional strategies that support executive function, focus regulation, and DMN balance. Research-backed approaches highlight structured work environments, proactive stress management, and self-awareness as key factors in maintaining long-term performance.

1. Creating Structured Yet Stimulating Work Conditions

ADHD adults thrive in environments that offer novelty but also provide structure to prevent disorganisation.

📌 Key Workplace Strategies for ADHD:

Stimulus control: Reducing distractions improves focus and minimises cognitive overload (Menon, 2011).

Scheduled deep-work sessions: Structuring work in concentrated blocks enhances engagement without inducing fatigue.

Flexible yet predictable routines: ADHD brains benefit from variety with clear frameworks to maintain productivity.

Noise-cancelling tools & digital organisers: These external supports help prevent environmental distractions from overwhelming attention networks.

A balanced work environment ensures that ADHD individuals can engage fully without falling into overstimulation or disorganisation.

2. Managing Hyperfocus Without Exhaustion

Hyperfocus can be both a strength and a risk. While it allows for deep concentration, it often leads to overexertion if not managed properly.

🧠 Sustainable Hyperfocus Management:

Time-limited work blocks prevent exhaustion and allow for consistent energy levels.

External reminders (e.g., alarms, coworker check-ins) help ADHD individuals step back before burnout sets in.

Frequent short breaks restore executive function and working memory (Buckner et al., 2008).

By harnessing hyperfocus in controlled bursts, ADHD professionals can maximise efficiency without depleting mental reserves.

3. Leveraging External Organisation Systems

Executive function challenges significantly contribute to stress and burnout in ADHD. External tools provide a way to offload cognitive effort, making workload management more sustainable.

📌 Recommended Support Systems:

Task managers & structured workflows: Reduce mental clutter and improve execution (Whitfield-Gabrieli & Ford, 2012).

Digital calendars & accountability partnerships: Help sustain consistent productivity without over-reliance on memory.

Checklists & automation tools: Simplify repetitive tasks, allowing ADHD professionals to focus on high-value work.

By using external scaffolding, individuals can reduce cognitive strain and sustain long-term performance.

4. Accessing Workplace and Social Support

Many ADHD adults hesitate to disclose their diagnosis due to stigma, yet workplace accommodations can significantly improve job sustainability and reduce stress.

💡 Key Workplace Adaptations for ADHD:

Flexible deadlines & alternative work structures reduce unnecessary executive function burdens (Castellanos & Proal, 2012).

Task-based rather than time-based performance evaluations accommodate ADHD’s natural work rhythms.

Mentorship and coaching support enhances skill development and confidence in high-pressure environments.

A neurodiversity-friendly workplace allows ADHD professionals to excel without excessive strain or risk of burnout.

5. Prioritising Rest and Hobbies for Long-Term Well-being

Sustaining high performance requires intentional recovery. ADHD brains benefit from engaging in activities that strengthen focus networks while preventing cognitive exhaustion.

📌 Effective Recovery Practices:

Physical activity (exercise, sports): Enhances dopamine regulation, improving attention stability.

Creative pursuits & outdoor time: Activate restorative cognitive states, preventing attention fatigue (Stern & Maeir, 2024).

Scheduled "intentional breaks": Prevents the DMN from hijacking focus unpredictably.

Taking purposeful rest prevents burnout and enhances long-term performance.

6. Professional Support: Therapy and Medication

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and ADHD coaching improve both symptom management and coping strategies.

🧠 Evidence-Based Interventions:

CBT restores disrupted DMN-attention connectivity, helping ADHD individuals manage focus and workload (Jönsson et al., 2022).

Medication, when appropriate, improves executive function and stress resilience, reducing the cognitive load required for daily functioning.

Seeking professional guidance provides tailored strategies to maintain sustained well-being.

7. Emphasising Self-Compassion and Cognitive Awareness

Above all, self-compassion is key. ADHD is not a deficit of capability but rather a difference in cognitive rhythm. Learning to balance DMN-driven creativity with structured focus can transform ADHD from a challenge into a strength.

Conclusion

Neuroscience has transformed our understanding of ADHD, with the Default Mode Network playing a critical role in both challenges and strengths. By recognising how ADHD brains oscillate between hyperfocus, stress, and disengagement, individuals can develop strategies to sustain high performance without burnout. High achievement and mental health are not mutually exclusive; with the right balance, an ADHD brain can thrive without burning out.

However, theory and practice often diverge. While research-backed strategies provide a framework for navigating ADHD in high-performance environments, finding a sustainable balance remains a personal experiment. The reality is that what works on Monday might fail by Wednesday. Productivity methods that help one week may feel impossible to implement the next. I have yet to discover the right balance between autonomous and structured work, between harnessing my ADHD strengths and not falling into burnout. It is an ongoing process of trial and recalibration, where the goal is not perfection but sustainability.

Ultimately, managing ADHD is about learning to ride the waves rather than resisting them—adjusting when needed, forgiving setbacks, and recognising that balance is not static, but fluid.

I will continue to experiment to see what actually sticks and doesn’t work temporarily. Let’s rewire together!

References

Ashinoff, B. K., & Abu-Akel, A. (2021). Hyperfocus: The forgotten frontier of attention. Psychological Research, 85(1), 1–19. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Cohen, J. R., Breiner, K., Steinberg, L., Bonnie, R. J., Scott, E. S., Taylor-Thompson, K., Rudolph, M. D., Chein, J., Richeson, J. A., Heller, A. S., Silverman, M. H., Dellarco, D. V., Fair, D. A., & Casey, B. J. (2021). Increased integration between default mode and task-relevant networks in children with ADHD is associated with impaired response control. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 15(4), 1718–1730. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Gao, Y., Shuai, L., Daley, D., Zhang, W., & Cao, X. (2019). Impairments of large-scale functional networks in ADHD: A meta-analysis of rs-fMRI studies. Psychological Medicine, 49(15), 2475-2485. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Jönsson, J., Unenge Hallerbäck, M., & Nilsson, K. W. (2022). Stress and work-related mental illness among working adults with ADHD: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 747. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Mowlem, F. D., Skirrow, C., Reid, P., Maltezos, S., Nij Bijvank, J. A., Merwood, A., & Asherson, P. (2019). Excessive mind wandering in ADHD: Development of a scale and exploration of its cognitive and neural correlates. Psychological Medicine, 49(3), 431–438. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Porto, C. C., Santos, R. B., & Pacheco, S. P. (2024). Prevalence and correlations between ADHD and burnout in Brazilian university students. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto, 34, e3413. https://scielo.br

Qian, J., Lin, H., Tang, Y., Li, Y., & Wang, X. (2024). Interference of default mode on attention networks in adults with ADHD. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Saad, M., Pineda, A., & Mattfeld, A. T. (2022). Intrinsic functional connectivity in the default mode network differentiates ADHD presentations. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Silberstein, R. B., Pipingas, A., Farrow, M., Levy, F., & Stough, C. (2016). Dopaminergic modulation of default mode network connectivity in ADHD. Brain and Behavior, 6(12), e00582. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Stern, P., & Maeir, A. (2024). Executive function deficits mediate the relationship between employees’ ADHD and job burnout. AIMS Public Health, 11(3), 399–412. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Yang, Z., Wang, Y., & Han, Z. (2023). Default mode network connectivity and social dysfunction in children with ADHD. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 23(3), 100360. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov