Pace of Disconnection: Building or Breaking the Next Generation’s Brains?

I never thought I'd include a piece about children and adolescents in this experiment. However, observing brain plasticity in adults and noticing my teenage brother—with ADHD and his unwavering infatuation with his phone and PS5—I couldn’t help but wonder about the neural foundations being laid through uncontrolled and excessive screen time. The more I pondered it, the more compelling it became. Despite a mere 15-year age gap, observing his social circle makes it feel as if four generations separate us. Millennials might have lacked the emotional maturity I now witness, yet there's a distinct emotional numbness evident among Gen Z. While various environmental factors play their roles, I'm specifically unpacking the neuroscience, exploring whether screen time holds benefits for early brain development. As cliché as it sounds and gosh, I never thought I would be saying this, children are indeed our future (-insert Michael Jackson reference)—understanding their neural wiring seems essential for systemic improvement.

What Heavy Screen-Time Does to Developing Brains

Excessive digital stimulation profoundly influences brain development during formative years (0–18), altering structural and functional maturation in areas crucial for cognitive control, emotion regulation, and attention. Chronic exposure to fast-paced, high-intensity digital media (e.g., rapidly edited videos, constant notifications, immersive games) may alter typical maturation patterns. Neuroimaging studies suggest that heavy screen media activity is associated with differences in gray matter volume and cortical thickness in youth (Hutton et al., 2019). A cross-sectional analysis of over 4,500 children in the NIH Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study found high screen use was linked to structural brain differences and slightly lower cognitive performance (Myers et al., 2023). Notably, children spending 7+ hours/day on digital devices showed premature thinning of the cortex, although such findings are correlational.

Why Are We Losing Our Focus?

Brain regions responsible for attention and impulse control—particularly the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and related networks—continue maturing through adolescence (Casey et al., 2008). Chronic digital overload may disrupt this maturation. Research shows the PFC, which enables impulse inhibition and focused attention, is one of the last brain regions to fully mature. Constant bombardment with digital stimuli (social media alerts, rapidly shifting apps, etc.) could adapt neural pathways toward distractibility. Frequent, long-duration screen use is linked to less efficient cognitive control systems, including differences in Default Mode Network (DMN) and Central Executive Network connectivity (Myers et al., 2023). Teens with heavier digital engagement have shown higher baseline cortical thickness in the lateral PFC but also accelerated thinning over time. Longitudinal research (2015–2022) tracking adolescents’ social media use and PFC development found accelerated cortical thinning correlated with heavier digital use. This means teens heavily engaged with screens may struggle more with staying focused, controlling impulses, and completing tasks without distractions, often feeling mentally exhausted and scattered.

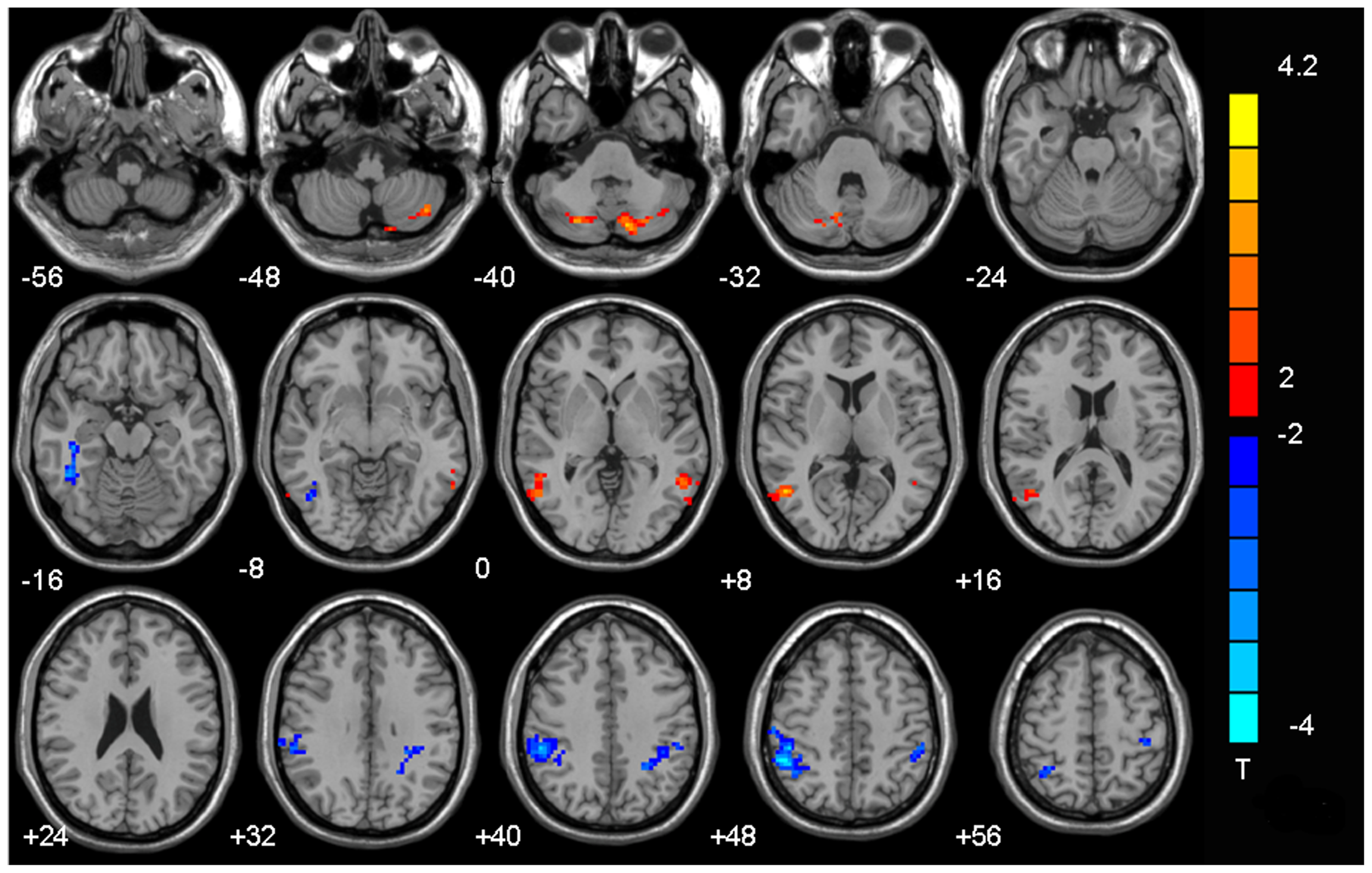

Figure 1.0

This brain scan compares teenagers with heavy internet gaming habits to those without. The coloured areas show significant differences in brain connections. Red areas indicate where teens with heavy gaming have increased brain connectivity, suggesting strengthened neural pathways related to habits, impulsive actions, and reward-seeking. Blue areas highlight decreased connectivity in these teens, suggesting weakened brain connections in regions responsible for attention, impulse control, and cognitive efficiency. Simply put, the red dots point to brain areas becoming overly active and impulsive, while the blue dots show areas becoming less effective at maintaining focus and control (Hong et al., 2013).

Why Are We Losing Our Focus?

Crucially, longitudinal evidence indicates that high screen exposure can precede attention difficulties. Dimitri Christakis and colleagues found that exposure to fast-paced TV in the first 3 years of life was associated with attentional problems at school age (Christakis et al., 2019). Animal models confirmed causality: overstimulated mice exhibited cognitive deficits and hyperactivity mirroring human findings, highlighting early childhood as a critical window for lasting neural impacts. Simply put, early excessive screen exposure might make children more easily distracted, hyperactive, and less capable of focusing in classroom and social situations as they grow older.

Regions involved in emotion and reward (amygdala, striatum, orbitofrontal cortex) mature during youth and can be shaped by digital habits. Interactive digital media frequently activate dopamine-driven reward circuits, strengthening incentive-driven neural pathways while potentially lowering boredom thresholds and complicating emotional regulation. Teens accustomed to immediate digital feedback may experience heightened irritability or anxiety offline. MRI studies indicate heavy digital users process emotions differently, though causality remains unclear (Panjeti-Madan & Ranganathan, 2023). Excessive screen time often displaces essential real-world interactions, limiting opportunities to build emotional resilience and self-regulation neural mechanisms (Christakis et al., 2019). In practical terms, this means that teens heavily exposed to digital stimuli might find it difficult to manage stress, regulate their mood, and self-soothe, making offline social interactions and emotional control challenging.

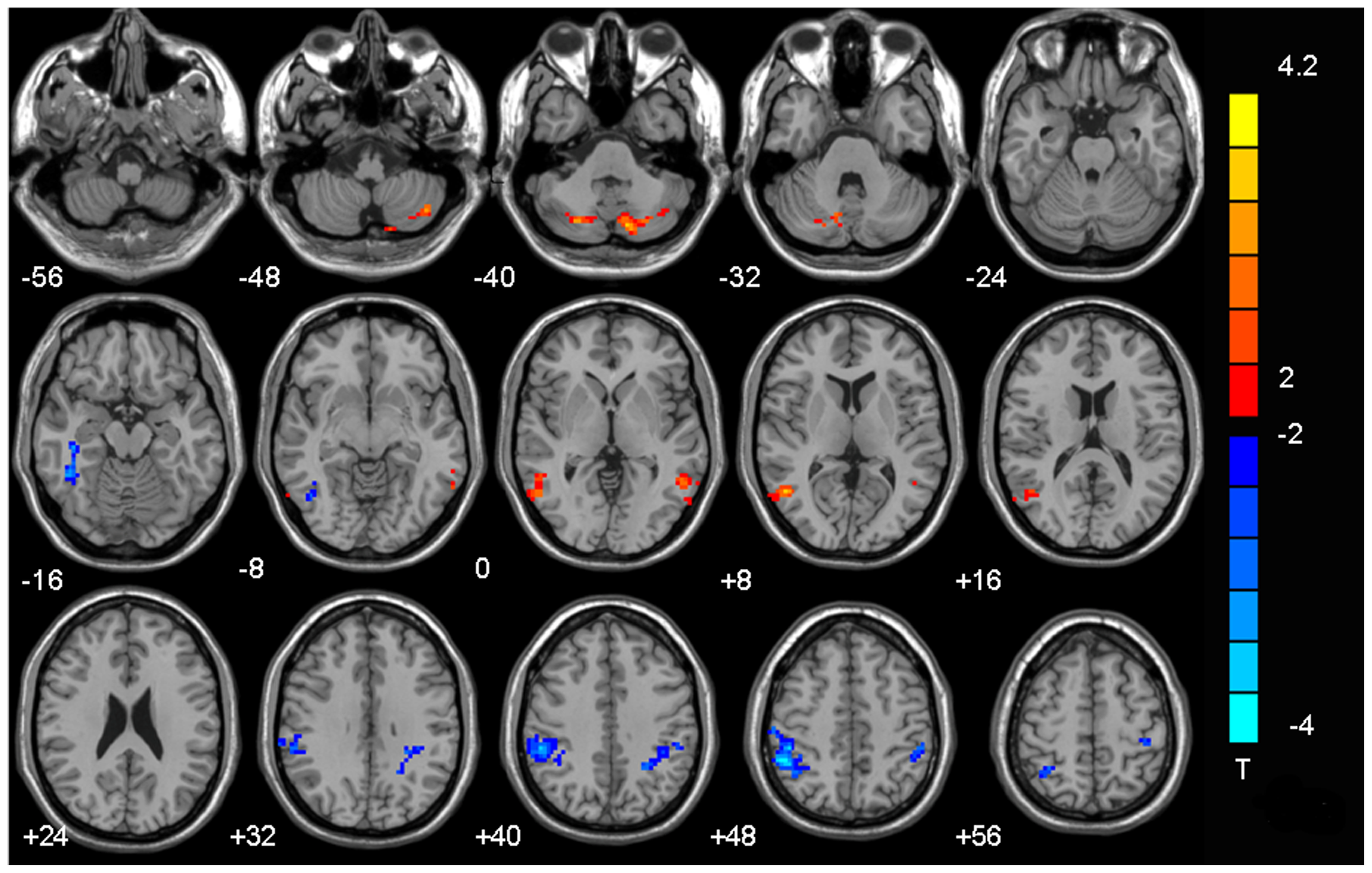

Figure 2.0

This brain image shows areas where connectivity significantly relates to the severity of Internet Gaming Addiction in adolescents. Red regions indicate increased connectivity, meaning these parts of the brain become hyper-responsive, reinforcing impulsive reward-seeking behaviour. Blue regions show decreased connectivity, suggesting weaker brain signals in areas responsible for emotional control and decision-making. In plain English, red dots mean the brain is overly driven to seek immediate digital rewards (likes, games, notifications), while blue dots mean it's less capable of effectively regulating emotions and making good decisions under stress or distraction (Hong et al., 2013).

Windows of Opportunity (or Risk): Why Timing Matters

Early childhood (0–5 years) and adolescence (12–18 years) represent critical windows. High screen exposure before age two has been associated with developmental delays in language and attention skills by preschool age (Domingues-Montanari, 2017). Adolescence involves significant synaptic pruning and myelination in prefrontal and limbic regions, strongly influenced by environmental inputs (Paus, 2005; Casey et al., 2008). Heavy multitasking might optimize neural circuits for rapid switching tasks but impair sustained focus. Balanced digital experiences, however, can enhance cognitive skills like visual-spatial abilities without detriments (Panjeti-Madan & Ranganathan, 2023). Simply put, moderate and thoughtful screen use during critical developmental windows might strengthen certain skills without harming overall focus and emotional control.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Neurotypical vs. Neurodiverse Children

Digital overload impacts neurodiverse children distinctly. ADHD youth may experience exacerbated impulsivity and distractibility from digital overstimulation, creating a feedback loop of worsening symptoms and screen dependence. A 2023 longitudinal study linked increased screen time to heightened ADHD symptoms through impulsivity erosion (Myers et al., 2023). For children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), digital environments provide structured communication aids but excessive passive viewing correlates with worsened social and developmental outcomes (Domingues-Montanari, 2017). Sensory sensitivities further complicate digital engagement, emphasizing mindful, curated digital use.

Thus, chronic digital stimulation shapes neural pathways for attention, reward, and emotional regulation. Developmental windows amplify vulnerability, particularly among neurodiverse youth. However, emerging research underscores the importance of balanced digital diets, advocating intentional screen-time limits and mindful parental involvement to support optimal brain maturation (Hutton et al., 2019; Myers et al., 2023; Panjeti-Madan & Ranganathan, 2023).

Let’s rewire.

References

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.010

Christakis, D. A., Ramirez, J. S. B., Ferguson, S. M., Ravinder, S., & Ramirez, J. M. (2019). How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: A review of results from observations in humans and experiments in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(40), 1902048116. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902048116

Domingues-Montanari, S. (2017). Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 53(4), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13462

Hong, S. B., Zalesky, A., Cocchi, L., Fornito, A., Choi, E. J., Kim, H. H., Suh, J. E., Kim, C. D., Kim, J. W., Yi, S. H., & Kim, Y. S. (2013). Decreased functional brain connectivity in adolescents with internet addiction. PLOS ONE, 8(2), e57831. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057831

Hutton, J. S., Dudley, J., Horowitz-Kraus, T., DeWitt, T., & Holland, S. K. (2019). Associations between screen-based media use and brain white matter integrity in preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(3), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5056

Myers, C. A., Smith, M., Gasser, C. E., Bader, L. R., Koren, D., & Kuhl, E. S. (2023). Children's screen time is associated with reduced brain activation during inhibitory control. Frontiers in Cognition, 2, 1018096. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcogn.2023.1018096

Panjeti-Madan, V. N., & Ranganathan, P. (2023). Impact of screen time on children’s development: Cognitive, language, physical, and social and emotional domains. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 7(5), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7050052

Paus, T. (2005). Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.008