Pace of Disconnection: The Cost of Presence in a Hyperconnected Era

The Great Illusion of “No Time”

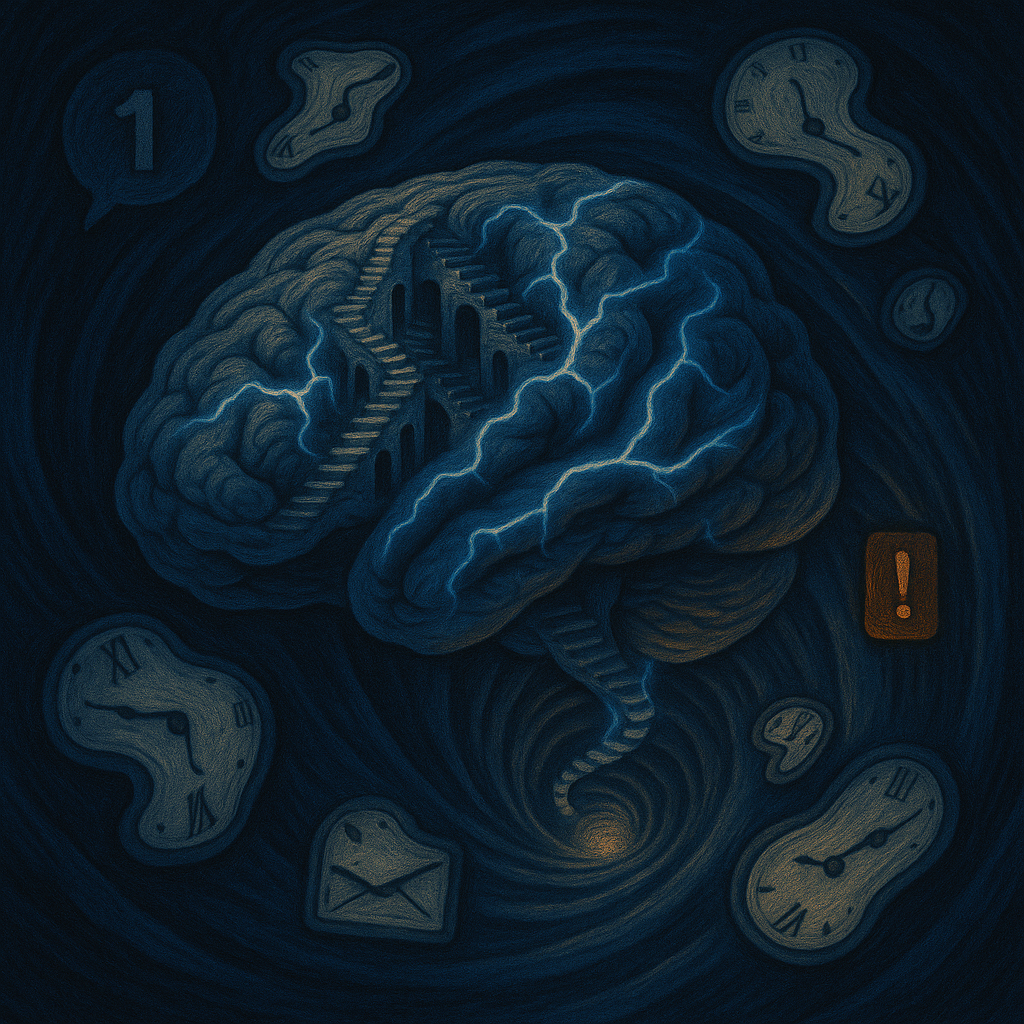

Taking a step back from purely intuitive living to squeezing more mechanical routines into my day has made me realise something rather unsettling. My life, it seems, has slowly but surely become centralised into one digital black hole—my phone. WhatsApp, Telegram, Slack—they promised to make our lives easier and our connections richer. But, as I already pointed out in the Innovation saga, layering shiny new tech onto outdated work habits is a guaranteed recipe for chaos. Ironically, despite every productivity hack I've ever sworn by, my to-do list just keeps mysteriously multiplying. My stubborn inner voice—the one I just can't silence—still whispers daily, "I don’t have time." Honestly, at this point, it could very well be humanity’s collective slogan, as we watch our precious hours dissolve into screens.

Constant connectivity produces an eerily convincing illusion of productivity. I don't know about you, but as I dash around frantically ticking off boxes, my days inevitably end up feeling reactive rather than proactive, no matter how meticulously I've planned. And planning, mind you, is meant to be my superpower.

Where Did The Day Go?

Time is a strange thing, shockingly malleable depending on where our attention lies. One moment I'm casually checking notifications, and two hours later, I'm wondering if I've entered a time warp. Neuroscience has my back here—this isn’t just me being dramatic. According to psychologists Zakay and Block (1997), our brains possess something called an "attentional clock," which tracks time neatly only if we're paying focused attention. But introduce the chaos of constant notifications, pinging chats, and endless browser tabs, and this internal clock gets utterly thrown off, drastically shrinking our perception of elapsed time (Wittmann & Paulus, 2008).

But wait, it gets better. Dopamine—the neurotransmitter famously responsible for pleasure and reward—plays a sneaky, extra role in distorting our sense of time. Every ping, every ‘like,’ every random notification sends tiny dopamine hits through our brains, accelerating this internal attentional clock. Suddenly, minutes slip away disguised as seconds (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2008). It's why "I’ll quickly check this notification" inevitably turns into a lost hour.

Dopamine Buzz

Digital overload doesn't just warp our perception of time; it also masterfully creates an illusion of accomplishment. Every small digital interaction, every email replied to, feels like a tiny victory for our dopamine-fuelled brains, making us crave these fleeting highs more and more. Studies show the striatum, a dopamine-rich area, lights up like Times Square when we're multitasking, chasing after short-lived rewards rather than engaging in the deeper, more meaningful tasks we actually intended to do (Wittmann & Paulus, 2008).

In simpler terms, our brains prefer instant digital gratification—answering that trivial email or liking a random post—over sustained, meaningful effort. And so, ladies and gentlemen, we have "productivity theatre," a spectacular display of busyness with no substance behind it.

To Multitask or to Not Multitask

Let’s cut to the chase: multitasking is not the holy grail as we are made to think although in my case.. hello ADHD it seems to be the only thing that keeps me productive in any way shape or form. However, the neurotypical brain’s prefrontal cortex—the CEO responsible for decision-making and task management—has strict limits. Multitasking forces it into a constant juggling act, rapidly switching between tasks, which drains precious cognitive resources and results in genuine mental fatigue (Levitin, 2015). While this juggling might feel productive, neuroscience tells a different story: multitasking actually slows us down and makes us far more prone to mistakes.

A fascinating (and somewhat depressing) study by Levitin (2015) clearly demonstrated that frequent digital interruptions significantly lowered actual productivity, even though participants felt they'd been working exceptionally hard. The takeaway? Multitasking produces a lot of mental activity, but disappointingly little progress. It’s the cognitive equivalent of running furiously on a treadmill and wondering why you're not going anywhere.

The Curse of the Open Loops (My Old Friend, Zeigarnik)

The Zeigarnik effect is my personal nemesis—the brain’s stubborn habit of obsessing over unfinished tasks far more intensely than completed ones (Zeigarnik, 1927). Digitally speaking, this means our minds are perpetually cluttered by half-written emails, unread notifications, unfinished conversations—essentially a mountain of mental tabs left permanently open. This creates a constant feeling of busy-ness, even if we're not truly accomplishing much.

I can feel that this has been my biggest challenge, I feel I get stuck into so many unfinished loops, even when I try to switch off – I find it impossible to. And the many notifications on my phone, even though I ignore them they just open more and more loops.

From a neuroscience viewpoint, these unfinished tasks monopolise valuable working memory, making the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus work overtime to keep track. This constant vigilance is perceived as stressful by the brain, which in turn nudges cortisol (the stress hormone) upward. It leaves us perpetually in that irritatingly familiar "wired but tired" state (Levitin, 2015). This stress drives us into endless after-hours "catch-up" sessions, further blurring the already fragile boundaries between work and personal life.

Understanding is Half the Battle

Thankfully, understanding the science behind this madness offers some hope. Simple strategies, like batching emails or setting focused, uninterrupted work blocks, can significantly lower dopamine-driven distractions. It provides your brain’s prefrontal cortex a well-deserved break, allowing you to regain control of your attention (Levitin, 2015). And mindfulness—despite its trendy, overhyped reputation—genuinely helps reinforce your brain’s capacity to resist impulsive multitasking, strengthening the neural circuits involved in attention and focus (Zhang et al., 2025).

Tomorrow, I will explore how this digital overload uniquely impacts the developing brains of children and adolescents. How are screens sculpting their cognitive development and emotional resilience? What might this mean for their futures—and ours?

Let's rewire.

References

Zakay, D., & Block, R. A. (1997). Temporal cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 6(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512604

Wittmann, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2008). Decision making, impulsivity, and time perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.004

Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2008). Affective neuroscience of pleasure: Reward in humans and animals. Psychopharmacology, 199(3), 457–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1099-6

Levitin, D. J. (2015). The organized mind: Thinking straight in the age of information overload. Penguin.

Zeigarnik, B. (1927). On finished and unfinished tasks. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A Source Book of Gestalt Psychology (pp. 300–314). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Zhang, Z. et al. (2025). Effectiveness of brief online mindfulness-based intervention on mobile phone addiction. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1400327.